Now Reading: Mastering UML Use Case Relationships: The Power and Peril of «include» and «extend»

-

01

Mastering UML Use Case Relationships: The Power and Peril of «include» and «extend»

Mastering UML Use Case Relationships: The Power and Peril of «include» and «extend»

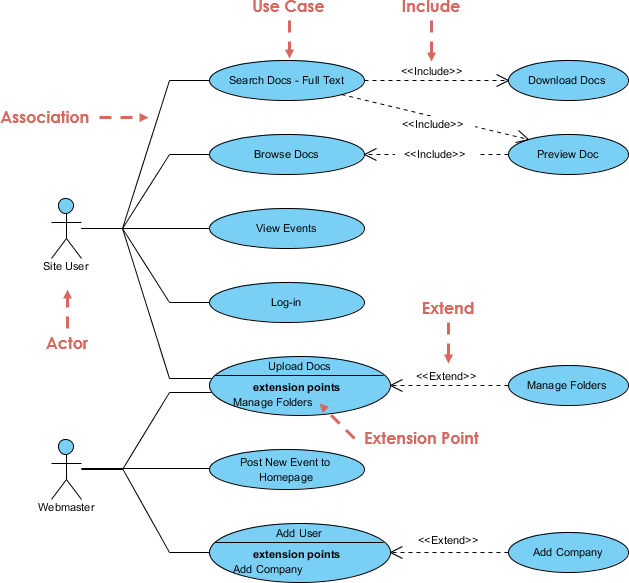

In the world of software requirements and system modeling, UML (Unified Modeling Language) remains a cornerstone for visualizing system behavior. Among its most powerful yet frequently misunderstood features are the «include» and «extend» relationships between use cases. These mechanisms are designed to reduce duplication, manage variability, and enhance modularity in use case models. However, their misuse is rampant—leading to overly complex diagrams, confusion among stakeholders, and a loss of focus on user value.

This article provides a comprehensive, practical, and expert-backed guide to understanding, applying, and avoiding the common pitfalls of «include» and «extend». We’ll explore their true semantics, compare them side-by-side, examine why they fall into the same trap as DFDs (functional decomposition), and offer modern best practices for 2025–2026 teams—especially those working in agile, lean, or hybrid environments.

🔹 Core Semantics: What «include» and «extend» Really Mean

✅ «include»: Mandatory Reuse – The “Always-Required” Sub-Flow

Definition:

The «include» relationship represents a mandatory, always-executed sub-flow that is factored out for reuse across multiple use cases.

📌 Key Characteristics:

-

Always executed: The included use case runs every time the base use case is invoked.

-

Base use case is incomplete without it: Without the included behavior, the base use case cannot fulfill its purpose.

-

Dependency direction: Arrow points from base → included.

-

Standalone meaning: The included use case is typically not meaningful alone—it only makes sense as part of a larger process.

-

Analogy: Like a function call or subroutine in programming—essential for the main routine.

🧠 Classic Mnemonic:

“To do Login, you must Authenticate User.”

“To do Withdraw Cash, you must Validate PIN.”

These are non-negotiable steps. You cannot log in without authentication. You cannot withdraw cash without validating the PIN.

💡 When to Use:

-

When a common, complex, reusable behavior appears in two or more use cases.

-

Examples:

-

Authenticate User -

Log Audit Trail -

Send Notification -

Validate Input Format

-

✅ Rule of Thumb: Use «include» only when the reused behavior is significant, non-trivial, and appears in ≥2–3 use cases.

✅ «extend»: Optional Variation – The “Conditional Add-On”

Definition:

The «extend» relationship defines optional, conditional, or variant behavior that plugs into a specific extension point of the base use case.

📌 Key Characteristics:

-

Conditionally executed: Only runs under certain circumstances.

-

Base use case is complete alone: The normal flow works without the extension.

-

Dependency direction: Arrow points from extending → base (backward).

-

Standalone meaning: The extending use case is almost never meaningful alone—it only makes sense in context.

-

Analogy: Like a hook, plugin, or AOP (Aspect-Oriented Programming) advice—it adds behavior at a defined point.

🧠 Classic Mnemonic:

“While doing Book Flight, you might want to Select Preferred Seat.”

“While doing Pay with Credit Card, you might have to Enter 3D Secure Code.”

These are optional enhancements—not required for the core flow.

💡 When to Use:

-

To model alternative paths, exceptions, or optional features.

-

When a use case has variant behaviors based on conditions (e.g., user roles, system states, preferences).

-

Examples:

-

Apply Discount(extendsPlace Order) -

Request Refund(extendsProcess Payment) -

Generate PDF Receipt(extendsComplete Transaction)

-

✅ Rule of Thumb: Use «extend» sparingly—only for meaningful variations with clear extension points.

🔍 Quick Comparison: «include» vs «extend»

| Aspect | «include» | «extend» |

|---|---|---|

| Execution | Always | Sometimes / conditionally |

| Base UC Complete Alone? | ❌ No — depends on included | ✅ Yes — complete without extensions |

| Dependency Direction | Base → Included | Extending → Base |

| Arrow Direction | Points to included use case | Points to base use case |

| Main Goal | Reuse mandatory, shared steps | Handle optional/variant flows |

| Analogy | Function call / subroutine | Hook / plugin / AOP advice |

| Standalone Meaning? | Rarely | Almost never |

| Best For | Reusable, complex, cross-cutting concerns | Conditional, optional, or alternative behavior |

⚠️ The “Decomposition Trap”: Why Use Case Diagrams Go Off the Rails

Just like DFD (Data Flow Diagrams) suffer from the functional decomposition trap, use case diagrams are prone to the same deadly disease: over-decomposition.

📉 The DFD Functional Decomposition Trap (Recap):

-

Teams keep splitting processes into smaller and smaller bubbles.

-

Diagrams explode into dozens of tiny, low-level functions.

-

The original purpose—delivering value to the user—is lost.

-

Ends up looking like pseudo-code or internal algorithm design, not user behavior.

🧨 The Use Case “Functional Decomposition Disease”:

-

Every tiny step becomes its own use case:

-

Enter Username -

Enter Password -

Click Login Button -

Validate Format -

Display Error Message

-

-

«include» is applied liberally to break down every action.

-

Result: A deep hierarchy of use cases (A → B → C → D…) with no clear actor goal.

-

Diagrams become unmaintainable, confusing, and useless to stakeholders.

❌ Red Flag: If your use case diagram has more than 15–20 use cases, or if most base use cases are 2–4 steps long, you’re likely in the trap.

🛠️ Why This Happens: Common Pitfalls & Misconceptions

| Pitfall | Explanation | How to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Overusing «include» | Treating every sub-step as a reusable use case. | Only use «include» for significant, reusable, cross-cutting behaviors (e.g., authentication, logging). |

| Confusing arrow direction | Drawing «include» arrows backward (base ← included) or «extend» arrows forward. | Remember: include = base → included; extend = extending → base. |

| Using «extend» for alternatives | Modeling alternative flows inside one use case as «extend» instead of using textual alternatives. | Use textual alternative flows for most variations. Reserve «extend» for true optional extensions. |

| Creating include chains | A → B → C → D → E… | Avoid deep chains. If you need multiple includes, consider refactoring into a single reusable use case. |

| Vague extension points | Adding «extend» relationships without clear, named insertion points. | Define explicit extension points (e.g., “After payment confirmation”) in the base use case. |

| Diagram clutter | Too many use cases and relationships → visual noise. | Keep diagrams small, focused, and actor-centric. Use multiple diagrams per subsystem. |

| Stakeholder confusion | Non-technical stakeholders find «include/extend» hard to grasp. | Use textual scenarios or user story maps for clarity. |

| Design-level modeling | Modeling internal architecture (e.g., “call database”) instead of user goals. | Stay focused on actor value—not implementation. |

| Endless debates | Teams arguing over “is it include or extend?” instead of writing scenarios. | Use practical heuristics and prioritize clarity over formality. |

✅ Best Practices for 2025–2026: A Modern, Agile Approach

The landscape of requirements engineering has shifted. Agile, lean, and product-driven teams are increasingly moving away from heavy UML diagrams in favor of lightweight, value-focused techniques.

🎯 Core Principle: Focus on Actor Value, Not Internal Structure

❗ Ask this question before adding any «include» or «extend»:

“Does this relationship help the user understand the goal, or is it just breaking down the system?”

✅ Recommended Modern Practices:

1. Use «include» Sparingly — Only for Major Reusable Behavior

-

Use only for cross-cutting concerns that appear in multiple use cases.

-

Examples:

-

Authenticate User -

Send Email Notification -

Log Security Event -

Apply Business Rules

-

❌ Avoid:

Enter Username,Click Submit,Validate Email Format

2. Prefer Textual Alternative Flows Over «extend»

-

Instead of:

«extend»: Select Preferred Seat → Book Flight -

Use:

Use Case: Book Flight ... Alternative Flow: 1. User selects "Preferred Seat" option. 2. System displays seat map. 3. User selects seat. 4. System applies seat preference.

✅ Why? Textual flows are easier to read, more flexible, and less prone to misuse.

3. Keep Use Case Diagrams Small and Focused

-

One diagram per actor or subsystem.

-

Limit to 5–10 use cases per diagram.

-

Use package diagrams or context diagrams to show high-level structure.

4. Ask: “Would a User Story Map Communicate This Better?”

-

If you’re using 10+ «include»/«extend» relationships, consider replacing the diagram with:

-

A user story map

-

A scenario-based table

-

A simple flowchart with key paths

-

🔄 Modern trend: Many agile teams avoid use case diagrams altogether or use them only for high-level discovery.

5. Use «extend» Only for Meaningful Variants

-

Reserve «extend» for optional, non-core features that:

-

Are rarely used

-

Are context-dependent

-

Are independent of the core goal

-

✅ Example:

Process Payment(base)

Apply 3D Secure Authentication(extend) — only when required by bank

❌ Avoid:

Enter Card Number→Validate Card→Process Payment(all should be steps in the same use case)

📊 Summary: The Golden Rules of «include» and «extend»

| Rule | Guidance |

|---|---|

| 1. «include» = Mandatory | Use only for essential, reusable steps that appear in ≥2 use cases. |

| 2. «extend» = Optional | Use only for conditional, variant, or rare behaviors. |

| 3. Base use case must be complete | «extend»: base works alone. «include»: base is incomplete without it. |

| 4. Keep it simple | If a use case is <4–6 steps after «include»/«extend», you’ve over-decomposed. |

| 5. Prioritize readability | Textual scenarios > complex diagrams. |

| 6. Avoid chains | No A → B → C → D. Refactor into one reusable use case. |

| 7. Know your audience | Stakeholders don’t care about «include» arrows—they care about value. |

| 8. Ask: “Is this a user goal or an internal step?” | If it’s not a goal for the actor, it probably doesn’t belong in a use case. |

🎯 Final Thought: Tools, Not Traps

«include» and «extend» are powerful tools—not rigid rules. They were designed to:

-

Reduce duplication

-

Manage variability

-

Improve maintainability

But like functional decomposition in DFDs, they become dangerous weapons when overused. The real danger isn’t the relationships themselves—it’s losing sight of the user’s goal.

🔥 Remember:

A use case is not a technical process.

It’s a story about what the user wants to achieve—and how the system helps.

When in doubt, ask yourself:

“Would a user understand this without knowing UML?”

If not, simplify.

If yes, you’re on the right track.

📚 Further Reading & References

-

UML Specification (OMG): www.omg.org/spec/UML

-

Martin Fowler – Use Case Modeling: Analysis Patterns & UML Distilled

-

Ivar Jacobson – The Object Advantage: Foundational work on use cases

-

Agile Modeling (AM) by Scott W. Ambler

-

User Story Mapping by Jeff Patton – A modern alternative to complex diagrams

✅ The One-Sentence Rule

Use «include» for mandatory reuse, «extend» for optional variation—but only when it truly adds value. Otherwise, keep it simple.

Because in the end, the goal is not to draw perfect UML diagrams—it’s to build systems that deliver real value to real people.

📌 Author’s Note (2025–2026):

As teams shift toward product-centric, value-driven, and collaborative development, the role of traditional UML diagrams is evolving. «include» and «extend» remain useful—but only when used with restraint, clarity, and purpose. Let them serve the user, not the diagram.

- What Is a Use Case Diagram? – A Complete Guide to UML Modeling: This guide provides an in-depth explanation of use case diagrams, covering their purpose, components, and best practices for modeling software requirements.

- Step-by-Step Use Case Diagram Tutorial – From Beginner to Pro: This comprehensive resource walks users through the process of creating effective use case diagrams, from basic concepts to advanced modeling techniques.

- Visual Paradigm – Use Case Description Features: This article explores the specific features available in Visual Paradigm for documenting user interactions and system behavior with precision.

- AI Use Case Description Generator by Visual Paradigm: This page details an AI-powered tool that automatically generates detailed use case descriptions from user inputs, significantly speeding up the documentation process.

- Automating Use Case Development with AI in Visual Paradigm: This article explains how the AI-driven generator reduces manual effort and improves consistency during the software development lifecycle.

- Visual Paradigm Use Case Description Generator Tutorial: A step-by-step tutorial that demonstrates how to automatically produce structured, detailed use case documents directly from your diagrams.

- Documenting Use Cases in Visual Paradigm: User Guide: This official user guide explains how to effectively document requirements using established templates and best practices within the modeling environment.

- Producing Use Case Descriptions in Visual Paradigm: This technical guide provides instructions on using the software’s built-in tools to create formal descriptions for system requirements.

- Demystifying Use Cases, Scenarios, and Flow of Events: This in-depth resource explains the critical relationships between use cases, scenarios, and the structured flow of events required for accurate documentation.

- How to Write Effective Use Cases? – Visual Paradigm: This tutorial highlights that the primary purpose of use case modeling is to establish a solid system foundation by clearly identifying user needs.